A Conversation with Jon J Muth

from Old Turtle and the Broken Truth by Douglas Wood from Old Turtle and the Broken Truth by Douglas Wood Cameron Brooks: Jon, thank you for taking the time tonight to speak with me. When I discovered your work as a first-year teacher, I realized that I need to seek out books that leave my students with more questions than answers. Without fail, your work becomes an immediate favorite for my students year after year. So, personally, this is a real treat.Jon Muth: Well, great. Thank you. CB: First, would you describe how Eastern art and philosophy entered your life, and your work? JM: I became interested in Asian art through the surface, down. I describe it that way. When I was very young, my mother — being an art teacher — would take us to art museums all over. I grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the museum there has a very nice art collection. Over a period of time, just seeing these pieces by Chinese painters and Japanese painters and calligraphers … there was a quality to the line that I found really engaging. I suspect it just wasn’t happening as readily in any other kind of art. It’s not that it wasn’t there, but it seemed to happen more often. Beyond saying that there was a quality to it that I found very authentic that really spoke to me, I can’t really describe it beyond that. There was something that was right about it. Of course, when I was really small I didn’t realize that I was seeing work from people in different parts of the world. I just saw different things on the wall. As I found this kind of work to be very engaging, and I ended up discovering, or wanting to discover, what kind of people made this work? What kind of culture produced this sort of artwork, and line work that spoke to me so strongly? So that led me to want to learn about the people and the culture. As you can see, I’m talking about it from the surface, and moving inward. That’s how it all began. And now, after having studied in Japan, and various teachers and so on, it’s just an expression of me. It feels like a very comfortable pair of pants.

CB: What was it like studying calligraphy and sculpture in Japan, compared to art programs here in the States? JM: Shodo, Japanese calligraphy, was pretty formal, but the apprenticeship was pretty informal. It was more of a type of partnership because I think not having a great deal of language skills in Japanese helped me. It became like the way teachers in China actually teach Tai Chi. They don’t talk. They simply move. You as a student follow them. They come over and adjust your movement to make it more in line with what you are supposed to be doing. I found it to be somewhat engaging for my whole body and mind. In a way, I don’t find that happening in the academic settings in the United States.

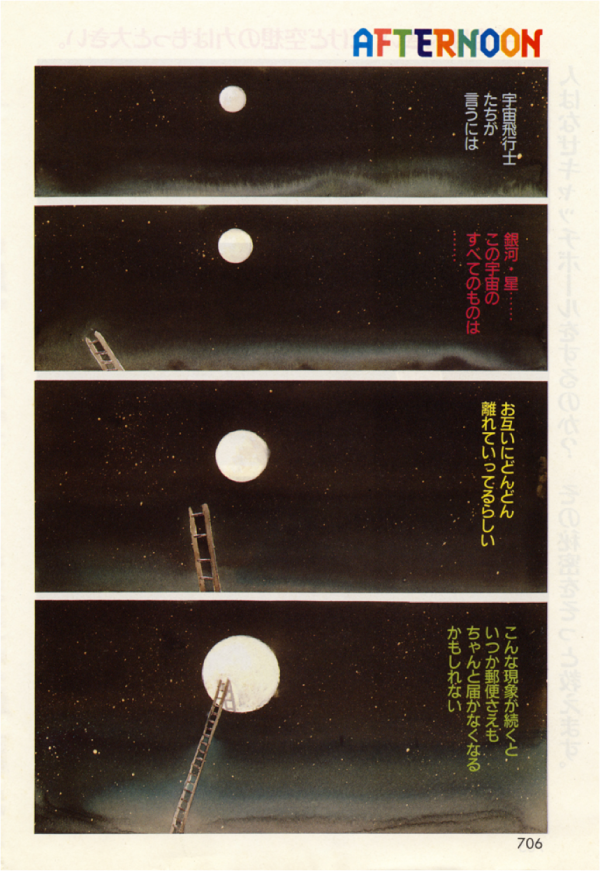

CB: Today I admired a Japanese comic you illustrated named Afternoon that included a cat following a boy floating in a bubble. JM: (Laughter) Thank you. That was a transitional period between working in comics, and then going on to work in children’s books. The name of the magazine was Afternoon, but the name of the story that you’re talking about is one of a series called “Imaginary Magnitude.” It ran for three years in theAfternoon magazine in Japan, eight pages every month. I was really fortunate to have come upon the publisher, who asked if I would be interested in doing something for them. At the time, they were looking for international artists to offer whatever difference we might bring to the table in terms of comics. I described what I wanted to do, which was a surreal story of a father and son. It gave me a chance to explore what it felt like to be a new father, and that’s how that whole body of work came about. CB: I found the illustrations to be amazingly fantastical and fun.

from Afternoon illustrated by Jon J Muth, Text © Muth/Kuramoto/Kodansha

JM: Well thank you. That’s the way it felt. It was nice that I was able to explore how it felt. It wasn’t without its darker sides, but at the same time, it has a lot of joy in it. There was a lot of room for that. Comics being printed and produced in the United States at the time were mostly a world full of Batman and Superman. CB: It seems more cynical. JM: Well, it certainly was at that point – definitely very dark and “film noir.” It had that feel to it, definitely cynical, but it works that way. I think the medium of comics ends up being a perfect form for, especially at the time, young men trying to find their way in the world, and expressing a great deal of angst about life and the things that they couldn’t understand. That was a sort of adolescent expression that worked very well as a form. Now, it’s thankfully grown into something more sophisticated and more inclusive, so we’ve got a lot of difference, which I applaud.

from The Three Questions by Jon J Muth

CB: Moving forward to your more current work, can you take us through the process of creating an image such as Leo the turtle handing Nikolai a cup of tea in The Three Questions? JM: Leo is a hermit in my story The Three Questions, and the story was originally told by Tolstoy. Your question itself is very difficult for me because I do so much of this without thinking about it; or rather I try to be as unselfconscious about it as possible. My process tends to be rather immediate, so I simply did a sketch. The boy had been outside helping to carrying a panda, probably bigger than he, to rescue it. Then he went out again to rescue the little panda that was stuck in the storm, so he was pretty tired. I just thought, “Well, what would Leo do? He’d probably offer him some tea and a blanket.” I did a little doodle that probably could have been done while having coffee in the morning, just a tiny, postage stamp-sized something to give myself an idea. Then my son Nikolai posed for the boy Nikolai in the story. So I had him sit still for some photographs, and that’s just what happened. I don’t tend to use a single photograph, I use them to look at and kind of combine them. Of course, I didn’t have a photo of a turtle serving tea. It came kind of easily, so I didn’t really think about it too much. CB: I wanted to know how it came to be, because that image is one of my favorites. JM: Oh, thank you. That one stays with me, too. I just happened to be there, so it was nice.

from The Stonecutter retold by John Kuramoto Click to see a video about the making of The Stonecutter

CB: Moving on to a different book, a more recent one… The fluid brush strokes in your recent book, The Stonecutter, present fleeting moments captured by very controlled detail. How do you find that balance? JM: I know it was published recently, but in fact, in this form, it was republished. The book was really done about ten years ago, or more. I had been working in Japan with brush a lot, so that’s really when that book was created. I was really happy that they reissued it though, because it was a really small run that they did the first time. I use very large Asian brushes and sumi ink. The brush tends to keep me from being able to provide a great deal of detail. The pictures that you’re seeing in that very small book are about 17 inches tall, so they were reduced a great deal. And the brush, if I ever did need some sort of small detail, I had to kind of splay the brush hairs until they would get small enough. I made that part of the crucible for that book (laughter). I was not going to use any white, and I was not going to use anything but one specific brush, and I was very happy with how that all worked out in the end.

In contrast to many children’s books that rush the child along, you offer moments to pause and reflect, almost like an exercise in mindfulness. Do you have any favorite such moments from your books? JM: No, I don’t think I have favorites. I hope that that’s there. I hope that that’s present. I hope the children are able to move through the book at the pace that I write it, and I read it. What you’re describing is great, because that’s what I hope happens. In each of the books, the Zen books and Stone Soup, it’s really just my verbal handwriting. In a way it’s really just my way of telling a story. Again, it’s not very considered. I just believe children are capable of intuitively grasping wisdom as readily as adults are. They just don’t have the vocabulary to be able to describe what it is that they’re finding. Those were the kinds of books that I felt were not being made, and they also happened to be the kind of books that I wanted. So that’s why they are there. CB: Whose work would you suggest to our readers? JM: Well now, when you say “our readers,” you’re talking about the people who read Literacyhead, right? CB: Right, teachers like myself who use art to teach literacy. So maybe books with a particular aesthetic that you enjoy. JM: Ah, that’s probably a little easier for me because the things I see on your site, they seem excellent, they seem to be doing what you’re describing. So as far as my personal aesthetic in books, I like Wolf Erlbruch very much. He’s a children’s book illustrator, and I think he’s in Germany. He’s in Europe, I know. Marvelous stories. I like his work very much. There’s also Lorenzo Mattotti, who has done children’s books and graphic novels. I think he’s doing some interesting things from Italy. There are things right here. Like, I read something to the kids tonight called “Boy.” I’ll have to check the author’s name, but it was just fabulous. It was just a picture book here. We’ve also got things like “The Quiet Book,” which, I think, is done by someone from Canada, but quite wonderful. So there are things happening right now that are right there in the store that you find yourself in. You don’t have to go hunting. I think Shaun Tan’s work is excellent. CB: I love Shaun Tan. He’s definitely one of my favorites. JM: He’s doing something exceptional, and very much his own voice, and that’s terrific. There are people doing very simple things as well, that I think are really excellent. Of course there’s Ed Young who’s always doing something different. He just always excites me. His stuff is just fantastic. He’s been working for quite a long time now. One of the first books he did — which I think is just fantastic, out of cut paper — is called The Emperor and the Kite. It was written by Jane Yolen. You ask this question and it opens up so much. I could just keep going. CB: I was hoping to get a few, to go out and look up, so thanks.

from Zen Ties by Jon J Muth

Our class begins each day with very simple chi gong or tai chi movements. JM: Oh, you do? That’s cool. CB: So the first time I read Zen Ties, and opened to Stillwater and Koo practicing tai chi, the connection for my students was immediate. JM: (laughing) Excellent! CB: In addition to Unkle Ry and Koo, can we expect to meet any more of Stillwater’s relatives in the future? JM: Well, you never know. Stillwater was really expected only to be in one story. I never intended to do a series, so it wasn’t until I was visiting my grandmother, who I’m going to go visit tomorrow, with my very young children. I was trying to find a way to describe what I was seeing, and what I imagined the relationship would be like if we lived closer. (This is a long-winded answer to what would have been a very nice closing question probably, but hold on.) CB: So do I. Uncle Ry is one of my favorite characters. JM: (laughing) Thank you. Well, being snow, you never know. CB: Now for my last question… This year’s batch of students is highly creative, and they can’t wait to hear about our conversation. In terms of creative discovery, what advice do you have for them? JM: I would suggest that they try with all their concentrated body and mind to be open to the present moment. You’ll find that there’s plenty to be amazed by. |

About this entry

You’re currently reading “A Conversation with Jon J Muth,” an entry on The Art of Living

- Published:

- April 27, 2011 / 6:38 pm

- Category:

- Children's Literature, Interviews

4 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]